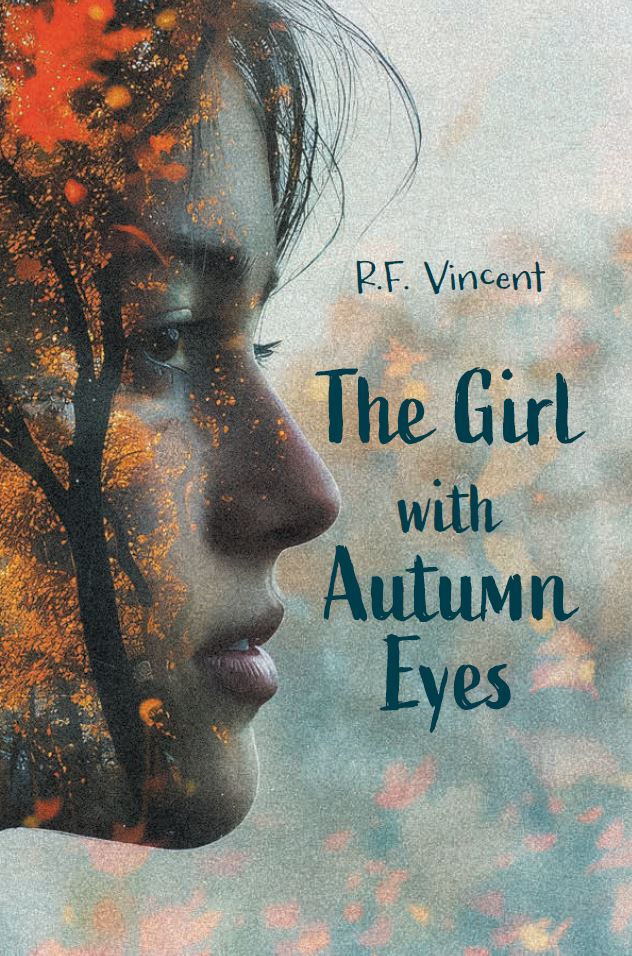

From the Blurb:

I looked at my watch—9:42 a.m. on the twenty-eighth day of September. It was the exact moment I fell in love with the girl on the bridge.

Discarded in a dumpster at birth and never adopted, MC has been crippled by social anxiety for most of his twenty-five years. Then one day, during an eventful bicycle ride through the Nova Scotia countryside, he has an improbable encounter with a woman on a bridge that changes everything. Although no words are spoken at the time, it’s love at first sight for MC. What follows is an entertaining and unusual quest for love. Despite his debilitating shyness and feelings of inadequacy, MC battles to break free of his self-imposed prison, leading to a remarkable journey that comes full circle in a way that no one could have ever imagined.

Smart, funny, and heartfelt, The Girl with Autumn Eyes is a spellbinding story of love and friendship that will stay with readers long after the final page.

Read the review

Chapter 1

The Girl on the Bridge

Nova Scotia, Canada, 1985

September!

Of all the months in the year, September is the one I get along with best. It’s not that I have anything against the other months. March and June have proven to be pleasant company over the years, and I even have a soft spot for February, who punched me in the stomach once. To be honest, I could strike up a conversation with any of the months. But there exists a special friendship between September and me. Why? It was September when I met the girl on the bridge. And you don’t share something like that without becoming close.

* * *

The first thing you should know about me, and the last thing I usually tell anyone, is that my life began in a dumpster. It was a frigid, snowy day in Halifax, Nova Scotia. A sanitation worker found me atop the refuse, blue and barely breathing. I survived the ordeal, but some people speculated that my odd behaviour as a youth was due to a lack of oxygen during my introduction to the world. I grew up in a foster home in rural Nova Scotia on the Bay of Fundy. The closest town was Mary Cannes Corner, which you’re not likely to find on a roadmap or in any self-respecting atlas. My formative years were characterized by a crippling social anxiety that followed me into adulthood. I’m in my twenties now, but the shy, frightened kid who couldn’t connect with anyone is still very much a part of me.

Working out of a tiny office in Wolfville, Nova Scotia, I’m involved in the sale of binzzbunzzers across the Maritimes. Binzzbunzzers are a type of office supply that falls somewhere between a poorly made paperclip and an inefficient clamp. Specifically, I’m the director of shipping and ordering, which is a somewhat inflated title since I’m the only employee in the office.

The town is quiet and picturesque with boutiques, restaurants and more trees than people. My days in Wolfville can be described as uneventful, mundane, routine. Except for one day. The most important day of my life.

* * *

It was a wild and windy morning in late September. The sun, a bright yellow splotch in a sea of blue, seemed warm and inviting but couldn’t fight off a nip in the air. It was officially cold outside, and the wind only made things worse. What made me classify the day as wild was the way the wind picked up an armful of leaves at any given instant and cast them skyward in a cloud of colourful confusion. There was neither rhyme nor reason to the wind’s swirling demeanour. It seemed to enjoy blowing the leaves this way and that, herding them into a corner, only to bully them into the open once more.

As I ate my traditional breakfast of puffed wheat, the radio DJ echoed my assessment of the day. “It’s a crazy, windy Saturday out there, folks. You better tie down your hat, or it’s going to get blown clear down to Yarmouth. But don’t take my word for it. Just ask The Association . . .”

The DJ didn’t have it right since the song was about a girl called Windy, not a windy day, but I enjoyed the tune, nonetheless. It made me want to meet Windy, who sounded like an interesting person. Just like her, I didn’t like liars, so that was something we had in common.

At the end of the song, I felt inspired enough to brave the wind on my bicycle. It wasn’t an ideal day for a bicycle ride. If the image in your mind’s eye is that of a day not fit for man or bicycle, an unpredictable and tempestuous day that could blow a person from under their hat and off their bicycle, then your eye is in its right mind.

One might say that only a true enthusiast of two-wheel exercise would cycle on such a morning while another may contest that only a madman would put foot to pedal in such conditions. Either way, I went.

To comprehend the significance of what happened next, it must be understood that I always took the same route when I rode my bicycle. It was a circular path that sent me down various country roads, most of which passed cozy little farms or wound amongst huge maple trees. I was on a first-name basis with many of the cows along the route, and the trees provided pleasant shade on the warmer days. But on that day, for reasons I’m still unable to explain, I decided to try something new—another circular route, but one of a different temperament, one that would send me to the top of a few large hills, through rugged hinterland, and maybe all the way to the Bay of Fundy, depending on my gumption. I had inexplicably decided on the route change as I wheeled my bicycle through the front door of my apartment building. Just like that. The break with tradition was out of character for me, and sometimes I wonder how my life would be different today if not for that odd impulse.

The bike ride began routinely. I was dressed in mittens, scarf, toque, long underwear, wool socks, track pants, turtleneck, and sweater, so I felt about as comfortable as the wind and my bulk would allow. After about ten minutes of cycling, in which my exposed face became numb to the elements, I settled into a steady cadence and began to enjoy the scenery.

I realized early on that my decision to change the route had been a good one. No traffic, lots of trees, green pastures, and friendly cows grazing in the fields. The wind had decided not to blow leaves in my face, opting to send them skittering across the road as though it were sweeping them under a giant carpet on the other side. The leaves were orange and red plus a myriad of colours like magenta and crimson, which probably don’t mean anything to most people but sound smart if you can slip them into conversation every now and then. The effect was dazzling, the type of feeling that can cast a person adrift in a sea of imagination. I pretended the leaves were multicoloured mice scurrying across the road. Sometimes my mind drifts like that—thinking leaves are mice or socks or Pop-Tarts or something very unleaf-like. This time they were mice, and it became a game not to run over them. I swerved this way and that, attempting to avoid collisions. It was fun for a while. I even seemed to be winning, rarely squishing any of the mice, until the wind became angry at losing and started blowing the mice in my face.

Drifting in a sea of imagination is an enjoyable excursion, but sometimes my mind doesn’t know when to drop anchor. Sometimes it realizes a fraction of a second too late that the leaves aren’t mice, that the mice are leaves, that a lot of them are blowing in my face, and if I don’t stop swerving, I’m going to end up in the ditch. That’s what happened this time. I found myself in a ditch full of water, leaves stuck to my tongue, a finger poking through a mitten, mud on my sweater, a scratch on my face, a rock digging in my back, and my bicycle on top of me. If I hadn’t hurt my leg, ripped my track pants, and left myself open to pneumonia, the whole ordeal would have been hilarious. I may have died laughing.

Undaunted, I picked myself up, brushed off my tongue, and pushed forward. I hated going back once I had started something. My leg throbbed in the vicinity of the knee, but I decided to work it out. I’d just go a bit easier. Nice and slow. No problem.

Then came a bark.

Another bark, only deeper.

That couldn’t be a third bark, could it? Yep.

I had a problem.

I glanced behind me and saw a platoon of dogs. They seemed to be in formation, as if they were in the dog military or possibly the reserves. The dogs of war, I thought, scarcely believing my predicament. One or two dogs I could understand—with three I’d be suspicious of a conspiracy—but there were eight or nine! Fresh from my tumble, I didn’t feel like a sprint. But self-preservation intervened, and soon I was pedalling with manic desire.

Much to my dismay, the pursuing pack was not out for a leisurely jaunt and appeared intent on tracking down their quarry. Led by a huge German Shepherd, the platoon kept pace for several minutes, even managing to gain some ground. But eventually, one by one, they fell by the wayside.

An overweight bulldog was the first to run out of gas, plopping himself in the middle of the road for a well-deserved nap. Then a wiener dog, whose legs barely reached the ground, wandered off as if he had never been interested in the first place. A Cocker Spaniel veered absent-mindedly into the trees, a Scottish Terrier tumbled into the ditch, and two mongrels halted their pursuit to fight each other instead.

I kept peering behind me, my heart lightening as the troops diminished. Only two left. Just the German Shepherd, who I considered the platoon sergeant, and a big old Boxer who looked as if he had been in a few skirmishes in his day. The two of them were tiring, their tongues almost dragging on the road. My odds of survival were increasing with every rotation of my pedals.

Happy with my improved odds, I swivelled my head forward, only to be greeted by a horrible sight. A relative of Mount Everest loomed in front of me. I couldn’t remember a hill with such a genetic background residing so close to Wolfville. It was the type of geologic structure that devoured bicycles, a monolithic hunk of granite that warped the road upward at an acute angle.

I tried pumping my legs harder, to no avail. I was slowing down. Slower, slower, slower—was I still moving? Despite standing on my pedals, my progress had all but halted. Sensing my difficulties and forgetting their own, the dogs moved in for the kill.

The German Shepherd got to me first and yanked on the leg of my track pants. I tried to keep my balance but found it impossible to remain upright and toppled over. The bike fell and slid part way down the hill. The Boxer grabbed a tire, then dragged the bike back up the hill toward me.

Sarge continued to gnaw on my track pants. He growled and snarled, pulled and tugged, dragging me in fits and starts down the hill. Thankfully, the big Shepherd didn’t have any of my flesh clenched between his teeth—just a mixture of polyester and cotton.

My initial reaction was to kick him with my free foot, but then I thought that might be an unwise provocation. Instead, I twisted around and slipped out of my track pants, though I lost a shoe in the process. Due to my sudden maneuver, Sarge flipped head over heels, but he still managed to maintain his grip on my pants.

The Boxer, who was beginning to realize that bicycles weren’t particularly appetizing, eyed Sarge’s prize. In a swift, snarling movement, he grabbed the free leg of my track pants. Sarge tugged. Boxer heaved. Then the pants ripped in half—exactly down the middle.

Lying in the center of the road in torn long underwear, I watched in amazement as both dogs darted back down the hill, each dragging half of my pants. Remarkably, Sarge had also managed to pick up my discarded shoe before departing.

I scrambled to my feet and collected my bike. Feeling it prudent to make myself unavailable for another attack, I ran up the remaining part of the hill, pushing my bicycle beside me. Once at the crest I mounted the two-wheeler and coasted down the other side. The cool air felt invigorating as it brushed past my face. The wind and leaves had settled down. I could still salvage the bike ride.

Ahead of me a rushing river gurgled under a bridge at the bottom of the hill. A car was parked on the far side of the bridge. Something old, something blue. A Chevette, perhaps. Then I saw a person on the bridge, leaning on the rail as they looked at the river below. It seemed peculiar that someone should stop in the wilderness to stand on a bridge.

Before I could ponder the mystery any further, I felt a bump, another bump, and then an even bigger bump—the undeniable symptoms of a flat tire. The Boxer must have chewed a hole in my tire. It was going to be a long walk back to Wolfville.

I climbed off my bicycle and looked toward the bridge, about fifty yards away. The person was unaware of my presence, staring at the water below, deep in thought. Even though they could conceivably give me a ride back to town, my first instinct was to walk in the opposite direction. It’s almost impossible for me to talk to people. I usually only speak when spoken to, and even then, I don’t say much. I’m always polite, but social situations make me anxious to the point of nausea.

I turned to leave, but there was something compelling about the individual on the bridge. I sensed that something was wrong. Amiss. Perhaps the car had broken down. I had a strong feeling that I shouldn’t abandon the person. Summoning all my courage, I walked toward the bridge, my heart aflutter, the splashing of the river concealing my approach. As I moved closer, the lower part of my long underwear, shredded from my encounter with Sarge, became lodged in my bike’s chain. Great. Now I could barely move.

Then I saw her.

The girl on the bridge.

And my life changed forever.

I looked at my watch—9:42 a.m. on the twenty-eighth day of September. It was the exact moment I fell in love with the girl on the bridge.

Love.

It was a sensation I had never experienced in my life. It struck me as a little absurd that I was mentally logging this information though she had yet to notice my arrival. The river below, thrashing out an autumn symphony against the rocks, absorbed her attention. And then I took stock of the state in which my disastrous bicycle ride had left me—one shoe, no pants, leaf-matted toque, torn mittens, scratched face, and tattered long underwear stuck in my bicycle chain. I realized I would strike her as more than a little absurd.

The river’s symphony allowed me to lift the bike and shuffle closer to the girl unnoticed. I stopped when I came within a few yards. I stared in amazement, awed by her beauty, my heart pounding. Then she looked at me. The thumping of my heart must have risen above the river’s crescendo and caught her attention.

She was startled by my presence, but not nearly as much as I expected. She simply smiled at me, a sad smile as though something weighed heavily on her mind. I’ll never forget the way she looked. It’s like a picture engraved into my brain, only it’s better than a picture—an image with dimension, sound, smell, as if the actual occurrence is trapped inside my mind. I smell the water, the leaves. I hear the river rushing below. A bird is chirping merrily in the woods. A squirrel scurries into the underbrush. A cool breeze caresses my face and kicks up her short dark hair, causing it to dance about her delicate ears. Her eyes are a reflection of autumn, warm and vibrant. Her smooth skin, slightly blushed from the briskness of the day, contrasts sharply against the blackness of her eyebrows. She’s wearing blue jeans, white sneakers, and a light grey sweater, everything perfect. A backdrop of intense fall foliage frames her angelic face. It’s so clear in my mind. A captured moment.

An instant later she was gone. She had taken notice of my dishevelled appearance and vamoosed. In the middle of nowhere, a woman should understandably bolt from such a strange character. And she did. Before I had a chance to say anything, she went to her car and drove away.

I felt like crying. I’d probably never see her again. Maybe she had a boyfriend or was married, but I wished I had said something—explained my predicament or at least mentioned the magenta and crimson leaves. I wished with all my heart that I had spoken to her.

I managed to liberate my long underwear from the bike chain and then limped toward home. I tried to forget about the girl on the bridge, but I couldn’t. There was something about her, some inexplicable quality that refused to leave my thoughts.

About halfway to Wolfville, a dark cloud drifted over me and began spitting huge drops on my head. It was a strange rain. The sun was shining everywhere else, but soon I was drenched and shivering.

As I slept that night, I dreamed of the girl on the bridge. Dreams are usually bizarre wisps of reality, but this one replayed our encounter precisely—smell, sound, colour, texture, everything. I tried to speak to her, but the words wouldn’t come out. I woke up with my heart pounding in my ears. As I tried to settle back down to sleep, her image persisted, clear and beautiful.

***

R. F. (Ron) Vincent is an award-winning author and a professor of physics and space science at the Royal Military College of Canada. In a previous career he flew as an air navigator with the Royal Canadian Air Force. In addition to scientific papers focusing on Arctic climate change, Dr. Vincent has published two other novels: Life at the Precipice, which won the 2023 Best Indie Book Award for literary fictionand made the long list for the 2024 Leacock Medal Award, and The Curious Mr. Pennyworth. He lives in Kingston, Ontario with his wife, JoAnne.

Leave a comment