Welcome to BookView Interview, a conversation series where BookView talks to authors.

Recently, we talked to Scott MacFarlane, about his writing and soon-to-be released book, WHO? (The Bone Shrine Crimes #2), a taut, gripping thriller steeped in corruption, murder, and a relentless quest for justice (read the review here).

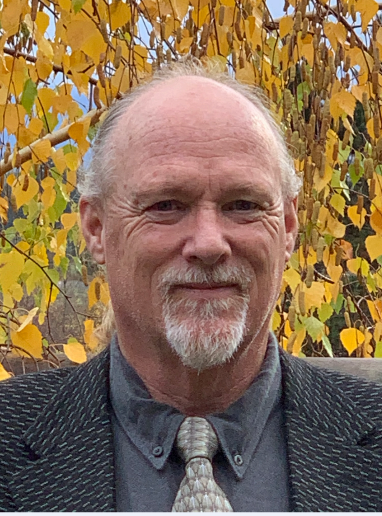

The author resides in the Skagit River Valley of western Washington with his ever-supportive wife, Brenda, also an artist. His key mentors include the outstanding novelists Steve Heller, Ron Carlson, and Tom Legendre. His personal threads of inspiration for The Bone Shrine Crime series include being a transit operator for 12+ years. A sundry flow of on-the-bus surprises often spark his muse.

The author served as the founding executive director of the Columbia Gorge Discovery Center in The Dalles, Oregon in the 1990s. He appeared in Paramount Pictures, “An Officer and a Gentleman,” in 1982 when he portrayed a U.S. Naval Air Officer candidate in Sgt. Foley’s (Lou Gosset, Jr.) platoon.

MacFarlane attended the University of Washington from 1974 to 1979, and Antioch University’s MFA in Creative Writing program from 2003 through 2005. In 1975, he spent his summer loading bushels of potatoes from the processing line onto boxcars at Basin Produce outside Moses Lake, also home of the actual Bone Shrine that inspired this series. As a senior in high school, the author was a Rotary International Exchange Student. He attended Katedralskolan in Linköping, Sweden. http://www.nicheeco.com

How did you decide on this title?

The Bone Shrine title came before I began writing my first draft of chapter one.

The satellite-setting on Google Maps allowed me to survey the shoreline of Moses Lake in eastern Washington so it might accommodate my rough biblical allegory suggesting a modern-day Joseph & Mary with Grace in the Moses Lake reeds. The reservoir itself showed no promise for this setting. However, the adjoining Potholes Wildlife Refuge had seep ponds fed by this same aquifer. It was there where I found a Google Pin near Interstate-90 a few miles west of the town. When I clicked, it said “The Bone Shrine.” Photos showed a circle of round river stones framing a disarray of bones. Nearby was the kind of reedy marsh I’d been searching to find.

My wife, stepson, daughter-in-law, and stepdaughter served as my focus group. This novel needed to be called, The Bone Shrine. “What else?” they all insisted.

The title, WHO?, was from the barrage of “So who killed Mary?” that came from many of those who’d finished Book One.

What was the easiest and most difficult part of your artistic process for launching your story and creating character depth in your narrative?

The Bone Shrine, Book One starts with one bad move turning Joe Gardner’s world on its head. His ‘rabbit-hole’ of addiction is deep and the loss of his sweetheart, Mary, even deeper. The narrative throughline focuses on Joe’s consequences––how the 18-year-old is forced to overcome a barrage of repercussions emanating from one singular life choice. Joe, struggling with his covert relapse, steals a highly valuable stash of heroin that he happens to find buried beneath the Bone Shrine altar near a remote, marshy pond. Physically, legally, and spiritually, Joe struggles in existential ways he never imagined.

For starters––even though he was filling a needed gas can at the nearest minimart, Joe’s charged with dealing the drug, drowning his teen sweetheart, and endangering her newborn, Grace, by placing the infant on an air mattress to float in the reeds of the Bone Shrine pond. Joe would be at the center of a major, public trial where he faces the consequences of decades in prison.

To my surprise, this daunting, opening dilemma came to me fairly easily, but I wondered how my protagonist would ever clear himself of his legal jeopardy. But other than those obvious legal benchmarks, my story wasn’t outlined beyond the opening scenes.

I needed to know more about Joe and Mary. I wanted them to be more three-dimensional––promising, coming-of-age 18-year-olds. So where did Mary and Joe come from to be very pregnant and car camping beside a Moses Lake pond and that eerie shrine of bones on a hot, August night?

Then it came to me. Write about what you know. The backstory for Joe and Mary would revolve around a project I knew intimately. The 18-year-olds would come from The Dalles, Oregon, two hundred miles downriver from the Columbia Basin. In the early 1990s, I directed the capital campaign and also helped provide the impetus for an Oregon Trail living history program in the summer of 1993 on the future site of the Columbia Gorge Discovery Center just outside The Dalles.

I envisioned Mary possessing an incredible singing voice in The End of the Trail Band. Joe was a wheelwright’s apprentice and, later, a caretaker of the raptors at the finished museum. This was where my narrative found its legs, the core characters their depth. From then forward, the crafting of this story flourished.

WHO? The Bone Shrine Crimes, Book Two was a natural outgrowth of Joe’s struggle. I hadn’t planned on a sequel, but maybe, subconsciously, I’d set the stage for “WHO?”

Near the end of Book One, I wrote an exchange between Mary’s best friend, Biff McCoy, and Captain Condran, the State Patrol officer heading up a special operation for solving the Bone Shrine crimes. Biff tells Captain Condran that she’s been accepted at Lewis & Clark, a prestigious college in Portland. When he congratulates her, she surprised him with a bold request. If Captain Condran allowed her to be his intern on the unsolved murder case, then the bright 19-year-old would enroll in the criminal justice program at Big Bend Community College in Moses Lake.

The bigger challenge in WHO?, Book Two wasn’t the plot that was firmly underway, nor the depth of characters, all of whom are well-established, but my need to capture a plausible first-person voice for Biff. (This is addressed below in another question).

Are any of your characters based on real people you know?/ How often did you base your characters on real people?

In the Bone Shrine Crimes series, there are roughly forty-five characters, many whom appear fleetingly. In Book One, The Bone Shrine, there are two viewpoint characters. Eighteen-year-old Joe Gardner is accused of murdering Mary Quinn, his teen sweetheart. His mother, Rochelle Gardner becomes dead-set on saving her son. The viewpoint character for Book Two, WHO? is Mary Quinn’s best friend, Biff McCoy. Of these three primary characters, only Biff is strongly based on the personality of an actual person I know. [Again, please see the next question for more on this.]

Several secondary characters are also drawn from real people, but the foreboding dilemmas surrounding the Bone Shrine crimes are fictional. The novels take place from August 2000 through April 2001 to coincide with the ages that Joe and Mary would be to have taken part in the living history program (age eleven), the grand opening of the museum (age fifteen), and coming-of-age at the Bone Shrine (age eighteen).

Kuma Kusumoto was a Japanese exchange student in the Gardner home. He, like Joe, is an excellent teen baseball player. Kuma’s also a practicing Nichiren Buddhist. His character is drawn from Hisashi ‘Kuma’ Iwakuma, former Seattle Mariner and the pitcher of a rare no-hitter for the team during the 2015 season. Iwakuma also practices Nichiren Buddhism. ‘Kuma’ means ‘Bear’ in Japanese.

Amanda Skerry, serves as the Child Protective Services (CPS) officer in both Book One and Book Two of The Bone Shrine Crimes. The real Amanda, an intermittent rider on my local transit route, was an actual CPS officer in her early thirties. She plays minor, compelling roles in both novels. In addition, she’s described as looking a great deal like Mary Quinn.

Both the prosecuting and defense lawyers involved in Joe Gardner’s trial were inspired by real individuals. Two women attorneys helped me imagine Judith Rose, the prosecutor in The Bone Shrine trial. One was a stiff, unhelpful attorney in eastern Washington who worked in a county office charged with establishing paternity, and also locating deadbeat parents owing back child support. This lawyer had no patience for my research. She was put-off when, for my novel, I wanted to know, hypothetically, what would happen if a mother from another state (Oregon) dies and the biological father is unknown.

I didn’t want Judith Rose to be overly two-dimensional, though. The chief criminal prosecuting attorney in Skagit County, where I live, named Rosemary, was a regular bus rider of mine for several years on her commute to and from Bellingham. I remember one compelling discussion she and I had while on the bus. We politely debated whether there should be a death penalty and she had me seriously weighing her opposing opinion. A year later I reminded her of this. “Oh, tell me again which side of the debate I took,” she said.

One night I happened to be watching NBC’s Dateline Show when it featured an episode from 2011, over a year before I began driving a transit bus. “The Dog Whisperer” episode examines the trial about an elite canine trainer from Skagit County who was murdered in 2009. “Hey look,” I told my wife, “that’s Rosemary!” The episode featured my bus rider prosecuting the homicide charges against the trainer’s ex-wife’s new boyfriend. The manner in which the chief criminal prosecuting attorney handled herself in court coincided with how I wanted to portray the prosecutor adjudicating Joe’s case. Rochelle, of course, had no sympathy for any lawyer charged with trying to send her 18-year-old away for decades. The eastern Washington attorney struck me as cold and unsympathetic, but imagining Rosemary in action helped me portray Joe’s prosecutor as coolly formidable, too.

Several Skagit County public defenders rode my same bus on the forty-minute commute from-and-to Bellingham. One of the public defenders was a particularly colorful man named Will. He would put his bicycle on the front rack of the bus after, too often, arriving a half-minute behind my scheduled departure. I could see him pedaling down the road, so I would wait. He always rode in with a square bucket on the rack above his rear fender. I’d wait for him to place his bike on our bus and remove the bungie cords so he could bring the container covered with offbeat stickers on board. He then took out his latest origami-in-progress to complete during our ride. Over the years, he gifted me occasional paper gems. Joe’s defense attorney––the Angus Macintosh character––was greatly inspired by Will. Despite the quirks, or perhaps because of them, I liked to imagine Joe’s lawyer as capable of seeing his cases in unique, innovative ways.

In The Bone Shrine, I wanted both the prosecutor, Judith Rose, and the defender, Angus, to be fine trial attorneys with very different personalities. In the novel, both prove impressive enough as trial lawyers to make the reader wonder whether or not Joe will escape his legal jeopardy.

The Honorable Mark O. Hatfield plays himself at the grand opening of the Columbia Gorge Discovery Center in The Dalles in May 1997. He was the ranking member on the Senate appropriations committee in 1994 when he secured the promised National Scenic Area funding essential for for building this interpretive facility. In a backstory scene, Oregon’s long-tenured US Senator has an engaging encounter with Mary Quinn and Joe Gardner at the tumultuous outset of the fifteen-year-old teens’ romantic involvement.

Jeff Stewart, a minor character, appears at the Gorge Discovery Center when Biff McCoy, in current story, sees her mother over Easter weekend, three-and-a-half years after the grand opening. Jill McCoy and this sculptor are discussing necessary, minor repairs to a seventeen-foot-long, black walnut sturgeon that Stewart, also the real life artist, had finished carving for the opening of the interpretive center, three years before.

Jill McCoy, mother of Biff, was based on Carolyn Purcell, the longest-tenured executive director of The Columbia Gorge Discovery Center and Museum after it was completed. In the Bone Shrine trial, Jill serves as a character witness for Joe Gardner. Throughout Book Two––WHO?––Jill McCoy’s worry for her daughter’s peril in the investigation never wanes. The mother’s instincts and concerns for Biff, who hides some of her predicaments, are not unfounded.

Captain Condran plays a major role in WHO? as the boss of his intern, Biff, when they investigate the case. Both Condran and Biff were inspired by two fellow transit drivers I worked with over the last dozen-plus years. [The two didn’t work at our transit agency at the same time and have never met.]

I enjoyed imagining my friend, Mark Condran, a former high school music teacher and fellow, long-suffering Seattle Mariner fan. I paint him as a Columbo-like detective who, as the Washington State Patrol special operations captain, must confront a daunting level of corruption and cover-up if he is going to solve the Bone Shrine crimes. Condran arrives near the end of Joe’s trial (The Bone Shrine) and stays on into the following year (in WHO?) to thoroughly investigate the cop-mangled case. In the sequel, Condran is forced, more and more paternally, to corral Biff’s indefatigable and impulsive drive. Biff McCoy’s insights are sometimes impressive, yet her penchant for peril alarming.

So, out of roughly forty-five characters in The Bone Shrine Crimes series, nine (or 20%) were, to a significant level, drawn from real people I’ve known.

Which character was most challenging to create? Why?

The most challenging character for me to capture was the first-person persona of Biff McCoy. In Book One, Biff arrives on the scene as Mary Quinn’s best friend. She was Mary’s confidante and serves the opening novel as a voice for the dead victim in a way that Mary’s boyfriend or the closest adults couldn’t. She and Joe have long competed for the attentions of Mary, but in their mourning, have come to realize how close they are. Biff knows Joe didn’t kill Mary, but sees how tough it will be to prove this. Book Two is overwhelmingly Biff’s story––one of obsession and persistence. Her resolve is instrumental in unearthing the truth of her best friend’s tragic fate.

Several years ago, my transit company hired three women in their twenties to train as bus drivers. Hailee, now an operations supervisor, decided to nickname Elizabeth, “Biff.” However, one day Elizabeth tried to pawn off the nickname on Brittany. In my observation, ‘Biff’ seemed to better fit Brittany. Consequently, this ‘Biff’––inspired by the vivacious and quirky Brittany–– shows up one-third of the way into Book One when she visits Joe in jail.

Book Two, WHO? presented a tougher challenge, though. I sensed that the best way to capture Biff as this unpredictable, 19-year-old sleuth/intern would be to channel her point-of-view through first-person narration. [Book One is written in third person limited, with sections of chapters alternating between Joe and his mother, Rochelle, in the viewpoint role].

Also, I recognized that Biff in Book Two would require me, a tall male in my late sixties, to channel a 19-year-old girl––short, unpredictable and coming-of-age. How would this bright, but immature intern approach solving the case? The trick would be to repeatedly ask myself what Britanny might do or say. Whatever confidence I mustered for this task stemmed from certain core personality traits that I shared with Brittany––ones that superseded our age and gender differences. Namely, she and I share gregarious and garrulous personalities with offbeat senses of humor and quirky behavior.

Last July 3rd, 2024, Brittany was on maternity leave and showed up at our bus barn nearly 10-months pregnant.

“So if your baby is born on the Fourth of July, will you be naming her ‘Sparkles’?” I asked.

Instantly, she flipped me off, to which I put my arm around her shoulder and wished her a smooth delivery.

Today, December 30, 2024, I’d hoped to see Brittany at work. I was alone, microwaving leftovers in the driver’s lunch room when the door to the Mamava Lactation Pod burst open and out popped Brittany. I showed her this Independence Day celebration photo. “May I use it for my author interview when they ask me for the most difficult character I had to write in my novel?”

“Sure. I don’t care, but she sure does look like Biff, doesn’t she?” said Brittany of the photo. [She is also one of my beta readers].

Were your parents interested in literature? Did they read a lot? What books did you have in the house?

I lived in Moscow, Idaho starting three months before JFK was assassinated when I was in 2nd grade through the first moon landing on the moon in the summer of 1969 following my 7th grade year. My mother earned a teaching degree at the University of Idaho when I was in 5th grade. Her mother had been a teacher, over half of my aunts and uncles, too. Mom taught 8th and 9th grade English for several years before earning a Masters of Librarianship at the University of Washington after her divorce had us living in suburban Seattle. She was the head librarian at a local high school for 18 years. We always had books in the home during my childhood and I went to the local Moscow public library quite often. Even though I never considered myself a bookworm, I did read steadily. I recall reading and loving Jack London’s Call of the Wild in 4th grade, Treasure Island in 5th grade, and most of Mark Twain’s works also starting in 5th grade. As an author, I’m most drawn to works of social realism that dare to ask the big questions. I’ve also gravitated to the voice in books by authors rooted on the West Coast such as London, John Steinbeck, and Ken Kesey, to name a few. My stepfather handed me Richard Brautigan’s Trout Fishing in America when I was sixteen. This featured absurdist, West Coast rooted irony like nothing I’d ever read––seminally postmodern I later came to realize.

After we moved to Seattle, my father would send us handwritten letters from Moscow, Idaho where he lived until he died. He’d graduated from the Univ. of Washington on a football scholarship and was the head track coach and physical education teacher at the Univ. of Idaho. He had a master’s degree in mathematics from Oregon State University. His track team won its conference championship in 1964. He was featured on Paul Harvey for how he taught a golf class. “For the rest of the story,” his instruction that day included hitting a hole-in-one in front of his students. Steve Brown was his high jumper from off the Idaho basketball team to whom he taught the ‘Western Roll.’ Brown won the NCAA national title in 1967. This was one year before Dick Fosbury introduced his highly radical ‘flop’ to win the gold medal at the Mexico City Olympics.

My father drew up the initial plans for a state-of-the-art outdoor track that was eventually built next to the covered Kibbie Dome football field on the Univ. of Idaho campus. Atlanta’s 1996 gold medal decathlete, Dan O’Brien, attended the U of I and trained on my father’s proposed, innovative track after it was built. When Dad left the Univ. of Idaho in the late 1960s, he relied on his carpentry skills as a one-man, house builder in Moscow. Not until years after I was grown did my father tell us he suffered from dyslexia and had a tough time reading and writing. As a kid, I never remember him reading a book or magazine article. Looking back, his primitive, handwritten letters were the first clue we had as his three kids. Later on in life, he described how he managed to get through four years to graduate at the Univ. of Washington, mainly by always attending class and paying very close attention to the lectures.

In 1989, the year before I began working on the Columbia Gorge Discovery Center project, my father gave me and my family two months of his time to help us build a house on five acres located behind a pear and cherry orchard outside White Salmon, Washington. The property faced south towards Oregon’s Mount Hood.

[As an aside, José, the father of Brittany’s two (very recent) children and also a fellow transit driver, grew up in this same, rural, Echo Glen orchard, three hundred miles from the Skagit Valley. Its the sort of serendipitous connection that unexpectedly and inexplicably fuels the magic of creating works of fiction.]

The reason I mention these details about my father is to suggest that the creative problem-solving disposition I have as an author may have come as much from my dad as from my mom. As his de facto apprentice for two months, I came to fully appreciate all the systems/components/constructive skills/day-to-day work plans/and creative alterations that are involved when building a house. The process, in many respects, parallels the crafting of any strong narrative. I was 33-years-old when helping build that home and had a tough time keeping up with my 60-year-old father during those long workdays. When this home with its incredibly strong ‘bones’ was complete, Dad had calculated our building materials so well that there were only a handful of sticks left in our construction pile of left-overs.

How did publishing your first book change your process of writing?

My first book, published in 2007, was a direct outgrowth of the critical thesis I wrote for my MFA in Creative Writing from Antioch University in Los Angeles (2005). The Hippie Narrative: A Literary Perspective on the Counterculture was the first academic book to use the literature relating to the 1960s/1970s youth movement as the lens for providing differing, key viewpoints on this baby boomer phenomenon.

For myself, as an author, writing a secondary text about other important works of literature doesn’t yield the artistic satisfaction that I garner from writing my own primary creations. The process of critical analysis is quite different than the generative process of tackling one’s own full-length work of fiction. Of late, I prefer to think of myself as a novelist.

After the writing’s finished, how do you judge the quality of your work?

This depends on how much I respect the person or entity providing me feedback on my prose.

For example, I was honored when a bus rider, one I’d carefully selected to be a beta-reader for the Bone Shrine Crimes series, told me that these were the best book he’d read in a year or more. He said, on the way to the methadone clinic, that he kept looking up and shaking his head in disbelief when he remembered that his bus driver was the one who had written what he was reading.

There were strong reasons I’d asked him to be a beta reader for the two novels. He was a constant and avid reader of quality books. I knew from conversations that he was well-educated. He was also in recovery, so I wanted to know if he thought that this aspect of my story rang true. Finally, he was eager to be a beta reader, so I sensed he would actually read the two books I gave him.

He’d also told me that he was a composer of music. One day when deep into reading WHO?, he looked up, suddenly. “Hey, Scotty, if your books get turned into a movie or mini-series, then I’d love to do the score,” he said. “That is, of course, if you have any say in the scoring.”

This sort of feedback made me believe that he sincerely believed in the promise of this novel.

***

Leave a comment